Many people who watch movies at home are irritated by black bars. Why are there black bars if the television is already widescreen, and why do some movies occupy the entire screen while others appear squished? Even stranger is the presence of black bars on the sides of older movies and TV episodes.

To further confuse spectators, some movies today, such as Zack Snyder’s Justice League, still appear in a boxy shape with black bars on the side.

Screen ratios are the image proportions on-screen, and this article will explain why movies and TV shows look the way they do and help you decide the best aspect ratio for your film.

The black bars that appear at the top and bottom of TV programs and movies can be aggravating. Some films have more black than others, while others have no black at all. Why isn’t filmmaking standardized yet, given that it’s been around for decades? There is no such thing as standard image size, believe it or not. It all relies on the aspect ratio in which the director wishes to convey the story. This article will answer some of your questions concerning missing parts of movies.

So, what exactly is an aspect ratio, you might ask?

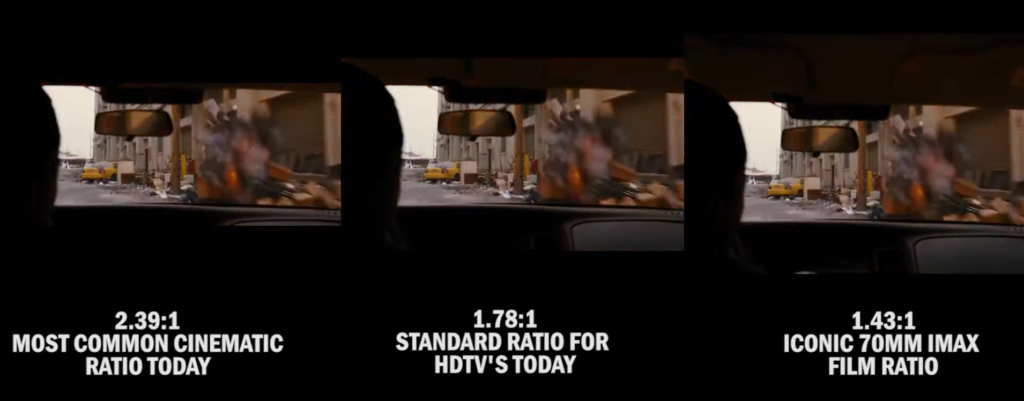

The proportion of the height and width of the image you’re viewing on a screen is referred to as the aspect ratio. Many films, for example, are shot in a 2.35:1 aspect ratio. This means that many movies have an aspect ratio that is two-point 35 times wider than it is tall.

Movies have a range of aspect ratios, although TV programs are usually shot in the 1.85:1 or 1.78:1 ratio.

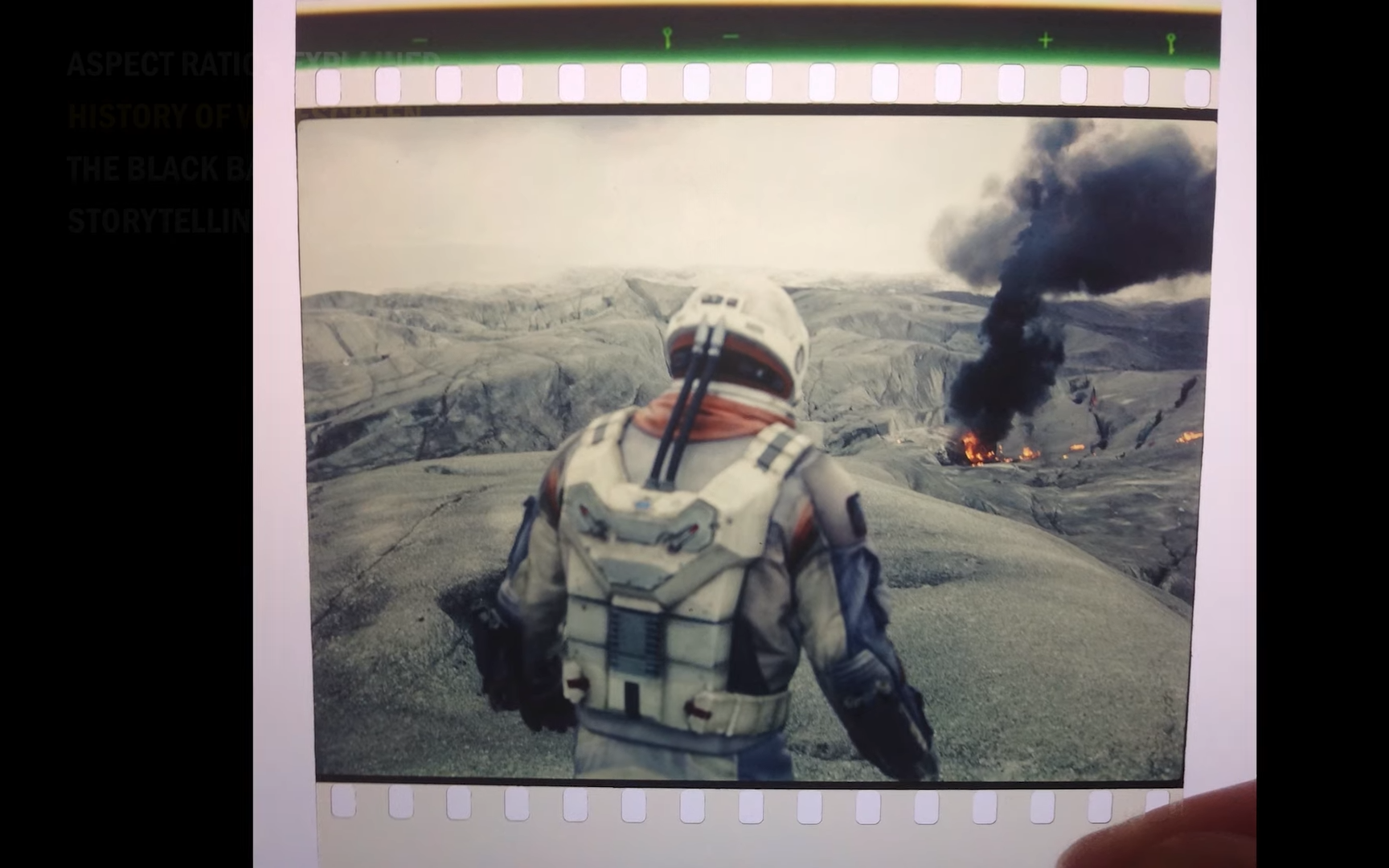

However, not long ago, nearly everything on TV and home media was in 4:3, forcing you to watch movies in theaters to see how the director wanted you to see their work. If you’ve ever seen a film cell, you’ll note that it has a boxy form to it. Initially, it was easiest to simply transfer images directly from film cells, modify them, and then display them on your television.

This explains why nearly all pre-2007 televisions have a boxy appearance. In the homes, there was no demand for widescreen content. Aside from a few film enthusiasts who desired them. With images captured in a boxy style, it seemed natural to display them on a boxy television to occupy the entire screen.

There is substantial debate about why movies began to be shot in widescreen. One explanation is that filmmakers wished to distinguish their work from that of television. One approach to accomplish this was to provide a wider viewing angle to the audience, as images in movie theaters are displayed on a larger screen.

The most widely accepted theory, however, is that movie directors determined that you don’t see the world in a box view. Because your eyes are so close together, you naturally experience the world in widescreen.

A brief history!

The Corbett Fitzsimmons boxing match in Carson City, Nevada in 1897 is the first documented widescreen recording. It was the longest picture at the time, lasting 100 minutes, and was made in a 1.65:1 aspect ratio.

Napoleon, the widest film ever made, was released in 1927. It had a 4:1 aspect ratio. Director Abel Gance used three 4:3 cameras adjacent to each other to capture the movie’s conclusion because there was no camera to shoot that wide.

The first attempt at standardizing the format occurred the same year when all major US studios agreed on a single 1.33:1 aspect ratio. The aspect ratio for 35mm film was determined in 1932 by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences and the Society of Motion Picture Engineers.

The “Academy ratio” was named after this new cinema standard, which was fixed at 1.37:1. Until 1952, all films were shot in this aspect ratio. The first wide-format movie feature to usher in the new widescreen era was “This Is Cinerama,” which premiered at the Broadway Theater in New York City in 1952.

Although it was more of a tech showcase than a film, it was the first time that viewers had the opportunity to see a widescreen film after the Academy ratio’s implementation.”

“This Is Cinerama” was shot with three 35mm cameras and exhibited on a very large curved screen with three 35mm projectors at a ratio of 2.65:1.

Anamorphic Lenses Created!

The demonstration was a success, and Hollywood began looking into new ways to make widescreen movies. This resulted in the development of the anamorphic lens, a technology that is still in use today.

Because it was impractical to always film with three cameras side by side, the anamorphic lens squished pictures onto the boxy film cells. When the images were repeated into a suitably fitted projector, they were incredibly wide.

The Robe, a 1953 film by 20th Century Fox, was the first to use this technique. The novelty of widescreen continued to grow, and several filmmakers pushed the concept even further. 2.76:1 is the biggest screen ratio ever used for an entire film.

It’s not often seen, but the first film to employ it was Ben-Hur in 1959, and it was used again recently in Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight.

16:9!

You could be thinking that none of these numbers are familiar to you. You’re probably used to hearing the number 16:9 when it comes to televisions. Televisions have always been measured in terms of two numbers versus the aspect ratio. Today’s televisions are all 16:9, with a 1.78:1 aspect ratio.

With so many aspect ratios available today, the electronics industry required a common TV screen size in order to sell to customers. Dr. Kerns Powers proposed a 16:9 ratio in 1984.

His research discovered that this ratio could easily display the boxy TV format and widescreen format to the human eye while also adequately displaying practically every other aspect ratio.

While Powers found this in the 1980s, it wasn’t until the late 1990s that the 16:9 aspect ratio became established for television.

16:9 is so ubiquitous now that when you record video on your cell phone or use a digital camera to capture family moments, it automatically records in the 16:9 format.

- Also Read- Who is a DIT on a film set? Responsibilities and How to be one!

- Also Read- 10 Best Learning Cinematography YouTube Channels for Amateurs!

- Also Read-10 Best Short Films on Mubi To Watch In 2022

How To Decide The Best Aspect Ratio For Your Film?

Now, the question remains! Which aspect ratio will be best for my film! A good understanding of aspect ratio can not only make your film look good but enhance and exaggerate the narrative as well.

All of this talk about aspect ratios is to get you thinking about how your decisions affect the production from start to finish, and especially to help you when you’re filming.

Make your choice wisely!

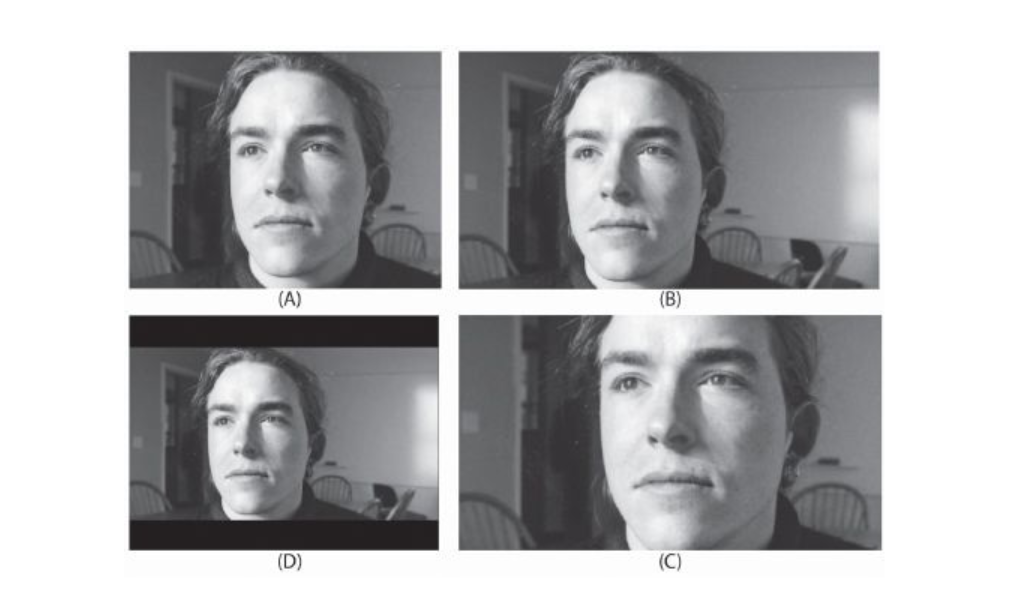

One thing to note about non-widescreen 4:3 is that it is perfectly suited to the proportions of the human face. A close-up of a person talking can neatly fill the frame. When taking a close-up of a face in 16:9, you have the option of cutting off the forehead or going wider and seeing more of the background.

When shooting in widescreen, you must pay special attention to how the person is positioned in the area of the room, as well as what else is visible around and behind the individual.

When choosing locations, styling them (placing objects or props), and selecting camera angles, make sure you’re taking advantage of the widescreen frame. When recording a single individual, it’s common to want to counterbalance the person with items or light elsewhere in the frame.

Widescreen formats are ideal for wide scenes with multiple characters or where the scenery is prominent. Widescreen formats are popular in the cinema because they make even little details visible when magnified on a huge screen. When widescreen films are displayed on smaller screens, details may be lost.

When seen in the theatrical Super Panavision 70mm prints at a 2.20:1 aspect ratio, the moment from Lawrence of Arabia in which a camel rider appears as a tiny on a wide expanse of desert and comes toward us is thrilling and gorgeous. The identical scene letterboxed on a small TV may leave you wondering what (if anything) is going on for a while.

Keep in mind when framing shots and blocking action if you intend to release a version of your film in a different aspect ratio. The way you modify is determined by the format you’re shooting in and the type of conversion you’ll perform. Although this study focuses on 16:9 and 4:3, the same ideas apply to other aspect ratio conversions.

Aspect Ratio Conversion!

If you shoot widescreen 16:9 and intend to make a letterboxed 4:3, you know the complete frame will be visible, but everything will be smaller. If there is something important for the audience to view or read in the scene, make sure it is large enough in the frame to be legible even when scaled down in the letterbox.

If you’re filming 16:9 and creating a 4:3 version using edge cropping, take care not to place key objects too close to the left and right sides of the screen (or, if you’re doing pan and scan, you can use either edge but not both at the same time). In 16:9, for example, it looks fine to have one character on the far left and one on the far right.

Once converted to 4:3, one of them will probably be cut off. A classic problem occurs when someone enters the frame from the left or right of the 16:9 version and on the 4:3 version you hear them before they enter the 4:3 frame.

The 16:9 and 4:3 versions of the frame share a “common top and bottom” while executing edge cropping, thus the headroom—the distance between the top of someone’s head and the top of the frame—is the same for both. However, the perspectives are diametrically opposed.

Conclusion

Understanding aspect ratios can sound difficult, but a good discussion during the pre-production with the Cinematographer and the editor of your film will save you tons of time. It will not only help your team understand your vision better but will also help them to modify their workflows according to the demand of the film.

Got a Question?

Find us on Socials or Contact us and we’ll get back to you as soon as possible.